|

Zora Arkus-Duntov: The Legend Behind Corvette

by Jerry Burton

Price: $49.95

|

As Excerpted in Autoweek, June 3, 2002

Zora had another agenda in those postwar years?that of establishing a reputation as a driver. Driving was his ultimate means of measuring himself and would rule the other major decisions he would make in his life. It was more important than engineering; in Zora's mind engineering was simply a means to drive. Combining the two brought Zora the ultimate in satisfaction. Nothing he could imagine would give him more fulfillment than driving his own machinery to a speed record or racing championship.

Zora's main stumbling block was that he had never really made a name for himself as a driver. His experience had been primarily with Asia Orley and his MGs back in the 1930s, and Zora was largely a backup to Orley. The Arkus project never got off the ground and didn't allow any opportunity for Zora to further hone his driving skills. In 1946 Duntov was 35, an age considered by many at the time to be over the hill. Despite his lack of driving experience, Zora was confident he could learn quickly.

With his rationale established, Zora decided to go for broke. Never willing to start at the bottom, he elected to apply his accumulated knowledge toward the most famous race in the world?the Indianapolis 500. And one of his employees at Ardun, Luigi Chinetti, could help him get there.

Chinetti was the Italian-American who later became synonymous with Ferrari. He was a multiple Le Mans winner (Alfa Romeo and Ferrari) and later imported Ferraris to the United States and headed up Ferrari's North American racing efforts. Zora met Chinetti for the first time in Paris in the 1930s when Zora was attempting to race the Arkus.

Chinetti was active on the local racing circuits in France, and at the time had planned to open up an exotic car repair shop. According to Stan Grayson, writing in Automobile Quarterly, he had come to America ostensibly to go to the Indianapolis 500 as chief mechanic with American Harry Schell in 1940 and was still in the States when America entered the war. Stranded in the United States, he remained in New York for the duration, then elected to stay in the States permanently.

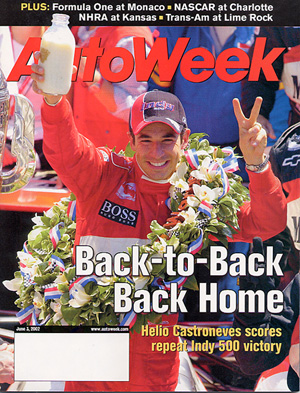

Like Chinetti, Zora was obsessed with the Indianapolis 500, the only race in America that garnered any real attention outside the country. Both were affected by the whole Indy mystique, from ?Back Home in Indiana? to the bottle of milk served to the winner of the race.

With a goal of entering the 1946 Indianapolis 500, Zora bought a prewar six-cylinder Talbot racer. As a grand prix car, the Talbot was never competitive. It ran against Mercedes and Auto Union but was hopelessly outclassed. Zora hoped that the Talbot might have better luck on American soil. The car became Chinetti's project while he was at Ardun and, like the old Arkus, also a Talbot, it was a project.

The 1946 500 was the first year the race was run following World War II. Zora felt that this could be an advantage in the fact that he wouldn't be competing against any established factory operations. The field would be dominated by prewar machinery. According to historian Donald Davidson of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Zora's Indy Talbot may have been the last race car at Indy to sport actual swinging doors, and it was one of 15 European cars entered that year.

The Talbot had a six-cylinder, three-carburetor naturally aspirated engine. Zora elected to race with the original engine because his own Ardun power plant was still under development.

Once committed to go to Indy, Zora contacted Speedway president Wilbur Shaw and asked for suggestions on a driving coach. Shaw suggested Cliff Bergere, an Indy veteran who finished third in the 1939 race. Since Chinetti was still preparing Zora's Talbot back in New York, Zora received permission from the Speedway to practice in one of Bergere's cars. But according to an April 29, 1946, letter from George Rodway on behalf of Wilbur Shaw, Zora was told, ?You must pass the driver's test in the car in which you will qualify and start in the race.? Bergere showed him all the basics, how to drive the fastest line around the track and how to handle traffic and pit stops.

Besides orientation at the Speedway, Zora had to prepare his Talbot for qualifying. Although he and Chinetti had rented a place in Indianapolis for the month of May, they didn't show up with the car at the Speedway until May 28, two days before the race. The Talbot had required more work than they bargained for.

Zora had to take a five-stage rookie test before he would be permitted an official qualifying attempt. The test called for doing ten laps of the two-and-a-half-mile Speedway within a prescribed minimum speed. The first phase called for maintaining 85 mph. The latter phases called for increasing speed in ten-miles-per-hour increments up to a maximum of 115 mph. Duntov passed the first phase, but on the second stage he spun out of control on the northeast turn and skidded onto the apron. Speedway officials were alarmed enough that he was not permitted a second qualifying attempt, and his hopes for running in the 1946 Indy 500 were over.

That same year, Zora ran the Talbot in AAA-sanctioned events on dirt tracks at Langhorne, Pennsylvania, and Goshen, New York. During practice in Goshen, Zora got into a dice with legendary dirt driver Rex Mays, with the two continuously switching places around the mile oval. Zora overcooked it on the straights and paid dearly in the corners, where Mays would eat him for lunch. ?Rex was high, wide and handsome in corner,? said Zora, ?while I jerky?accelerating and braking.? Finally, the AAA officials called them both in and said if they used the same techniques in the race, mayhem would result.

So far, Zora had done nothing to distinguish himself as a driver. He was not smooth and consistent, but rather overaggressive and jerky, a sign of his inexperience. He had discovered the great difficulty in trying to be a great engineer as well as a great driver. Often the two didn't mix because excellence at either endeavor demanded a total commitment, something Zora wasn't prepared to give. He may not have had the temperament to be a great driver, but whatever limitations he possessed, he never stopped trying.

At Langhorne, Duntov arrived for the first time during practice and had to wait to cross over to the inside of the track. Watching the careening machines kicking up rooster tails of dirt as they lapped, he thought, ?I must be crazy to enter this race.? Once on the track, however, the impression of speed went away, and he immediately liked the fact that the response of the car was much slower and steering with the throttle provided a feeling of complete control. Zora liked the dirt best when he was the only one on the track and didn't have to eat the mud flying off the tires of the other cars. He also raced an Ardun-powered sprint car at Union, New Jersey. Once again, he achieved nothing remarkable at any of these venues.

He liked the dirt enough, however, to enter Pikes Peak, the most famous hill climb in North America. Duntov submitted an entry form dated July 31, 1946, listing himself as the driver and Luigi Chinetti as his mechanic. But Zora would only go if the Pikes Peak Hill Climb Association organizers were willing to offer appearance and transportation money. They weren't, and informed him so in a Western Union telegram dated August 21, 1946. A Duntov rendezvous with Pikes Peak would have to wait a few more years.

In 1947, Zora and Chinetti went their separate ways, with Chinetti pursuing an effort to drive an Alfa Romeo. Zora returned to Indy with the Talbot and a new chief mechanic whose last name was Ladd. They submitted their entry as ?The Martin Special.? The car was actually sponsored by the Cornelius Printing Company of Indianapolis at the request of Speedway president Wilbur Shaw. Exactly how the sponsorship came about isn't known, but it's likely, says IMS historian Davidson, that Shaw went to his friend Pem Cornelius and asked him to help Zora as a means of assuring the car got to the track. The sponsorship probably amounted to less than $250.

This time, Duntov appeared at the Speedway four days before the race to resume the rookie test at the 95-mph phase. He passed that and was running 103 mph on the third phase when the car quit. Once again, his hopes to compete in the Indy 500 were dashed.

After the 1947 race, Shaw wrote a letter to Zora in which the subject of Zora's Talbot came up. ?I do not know what to recommend about the Talbot; she is a little bit short of steam to make any money out here. I think it would be advisable if you can get anything out of it to let her go.?

In November of that year Duntov followed Shaw's advice and sold the Talbot to Harry Schell, a blue-blooded American born in Paris of well-to-do expatriate parents. He would later become the only American in grand prix racing, driving for a succession of different teams, including Cooper, Gordini and Ferrari, but he never won a grand prix in his 14-year career.

Schell got to know Duntov in New York and the two became close friends. Schell offered to buy the Talbot for $5,000. Zora accepted, which put an end to his days as a race car owner. He and Schell would cross paths again soon, however.

Zora never let go of his dream to compete at Indy. For the rest of his life he was an annual visitor to the track and maintained close friendships with Wilbur Shaw and later the Hulman family. But his heart ached at the fact that he was never a part of ?the greatest spectacle in racing.? He would have to make his mark in the world in a different way.

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)