|

Equations of Motion -

Adventure, Risk and Innovation

Price: $39.95

|

Mountain Home Magazine - September 2012

History's Turn at Milliken's Corner

Before Busch and Gordon, Watkins Glen was wowed by Linton and Milliken, and the 1948 crash that started it all - By Brendan O'Meara

This story starts with a crash the Day the Trains Stopped and ends with the boy who saw it all.

Local auto clubs raced a bit in the 1930s, but had taken a brief hiatus prior to World War II. The military needed gas and metal, so road racing fell off. The only racing this country could watch involved a field of horses and the hope that maybe Citation would win the 1948 Triple Crown, which of course he did.

But in that same year, as Citation dominated the Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, and Belmont Stakes, a group of men drew up plans to give re-birth to American road racing through the streets of Watkins Glen.

Thanks to sports car enthusiasts the late Cameron Argetsinger, the late Bill Milliken, and Otto Linton, the course sprung to life on the village streets of Watkins Glen, 6.6 miles looping in the shape of a malformed eggplant. Bill Green, of the Motorsports Research Center, said, "The circuit was made of concrete, black top, oil and stone and gravel. It was long. There was a railroad crossing and an underpass."

But the train ran every hour. This posed a problem for the junior prix and the senior Grand Prix. The mayor of Watkins Glen approached trainmaster Frank Close and wondered, well, is there something we can do about this train?

- We'll just reschedule the train.

And so he became known as the "Man Who Stopped the Trains" on October 2, 1948. There'd be eight laps for 52.8 miles of high-speed and engine-roaring fun to signify the dawn of a new era. Racing was born again.

Green was eight years old that day while he watched the race from the How-Gay Tavern. His father was into harness racing for horses, but this rebirth of road racing, this was something alien, this was cool-uncle cool. "In rural America you go to an event like a road race renewal, it's a big deal. It's like the Fourth of July. My mom said, 'Do you want to come to the auto race?' I was very thrilled. That stuck with me forever."

Frank Griswold won the race on the Day the Trains Stopped.

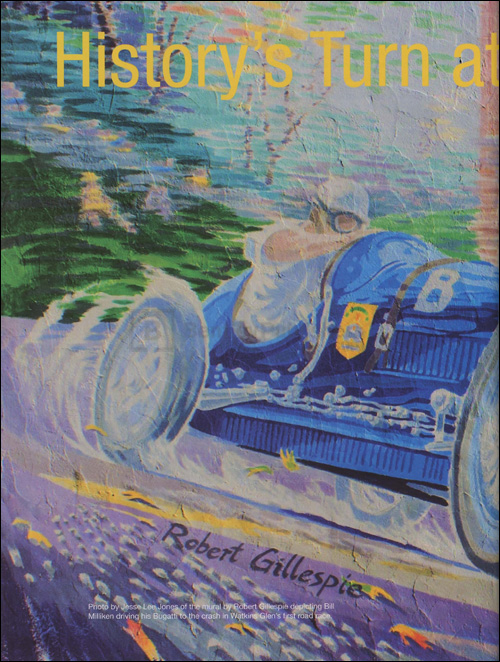

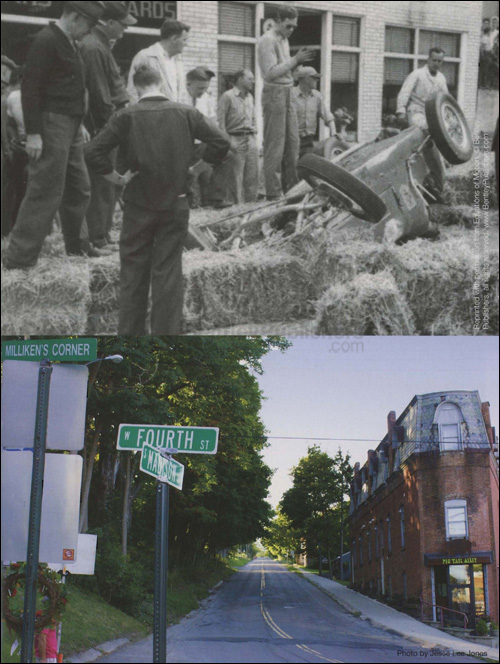

As for Bill Milliken? He rolled his car at 'Thrill Curve, 6.2 miles into the circuit. Milliken crawled out of his Bugatti to the cheer of the crowd with nothing but a scratch on his arm.

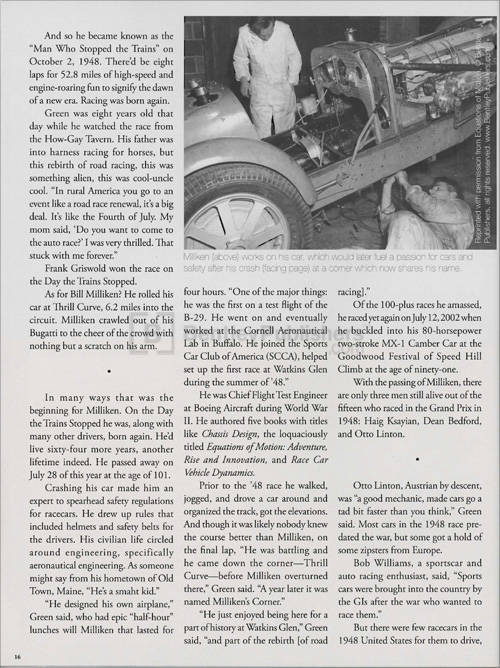

In many ways that was the beginning for Milliken. On the Day the Trains Stopped he was, along with many other drivers, born again. He'd live sixty-four more years, another lifetime indeed. He passed away on July 28 of this year at the age of 101.

Crashing his car made him an expert to spearhead safety regulations for racecars. He drew up rules that included helmets and safety belts for the drivers. His civilian life circled around engineering, specifically aeronautical engineering. As someone might say from his hometown of Old Town, Maine, "He's a smaht kid."

"He designed his own airplane," Green said, who had epic "half-hour" lunches with Milliken that lasted for four hours. "One of the major things: he was the first on a test flight of the B-29. He went on and eventually worked at the Cornell Aeronautical Lab in Buffalo. He joined the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), helped set up the first race at Watkins Glen during the summer of'48."

He was Chief Flight Test Engineer at Boeing Aircraft during World War II. He authored five books with tides like Chassis Design, the loquaciously titled Equations of Motion: Adventure, Rise and Innovation, and Race Car Vehicle Dyanamics.

Prior to the '48 race he walked, jogged, and drove a car around and organized the track, got the elevations. And though it was likely nobody knew the course better than Milliken, on the final lap, "He was battling and he came down the corner - Thrill Curve - before Milliken overturned there," Green said. "A year later it was named Milliken's Corner."

"He just enjoyed being here for a part of history at Watkins Glen," Green said, "and part of the rebirth [of road racing]."

Of the 100-plus races he amassed, he raced yet again on July 12, 2002 when he buckled into his 80-horsepower two-stroke MX-l Camber Car at the Goodwood Festival of Speed Hill Climb at the age of ninety-one.

With the passing of Milliken, there are only three men still alive out of the fifteen who raced in the Grand Prix in 1948: Haig Ksayian, Dean Bedford, and Otto Linton.

Otto Linton, Austrian by descent, was "a good mechanic, made cars go a tad bit faster than you think," Green said. Most cars in the 1948 race predated the war, but some got a hold of some zipsters from Europe.

Bob Williams, a sportscar and auto racing enthusiast, said, "Sports cars were brought into the country by the GIs after the war who wanted to race them."

But there were few racecars in the 1948 United States for them to drive, certainly none of the caliber the Euros had designed, and no automobile racetracks. They'd have to make do with mapping out public streets as they would in Watkins Glen.

"I was asked to give my impression of the course and the possibility of getting enough entrants from the club's members of only a couple year's existence," Linton said. "I drove and found the 'track' quite challenging with partially going through the then-sleepy village. But my feeling was that it would be worthwhile for the town to grow. This is history."

Otto Linton motored around the course that took him first under the railroad tracks, over Sonte Bridge, then over the railroad tracks, past Friar's Corner, by the corner-that-would-be-named-after-Milliken, and breezed by the eight-year-old Bill Green before finishing where he began at the Court House.

"The race of 1948 was to be the first official race to be sponsored by SCCA," Linton said, "the first such race post war. Previously there have only been a few club races staged in the 1930s. The race came off very well because of the close friendly relationship of the competitors. We all knew each other and did compete in a very sporty way. Although there were a couple of minor accidents involving only the cars, no personal injuries. It brought spectators in who had never heard of the beautiful Glen and became friends of the town and the lake."

Because of this race, "Gradually the sport of car racing spread over the whole country, with tracks in almost every state," Linton said.

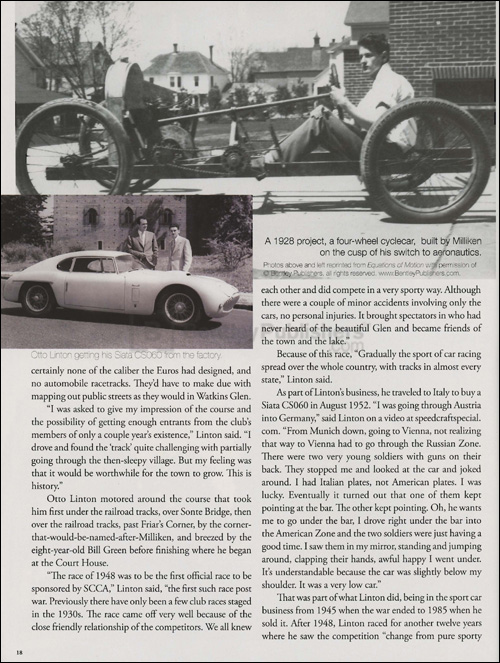

As part of Linton's business, he traveled to Italy to buy a Siata CS060 in August 1952. "I was going through Austria into Germany," said Linton on a video at speedcraftspecial. com. "From Munich down, going to Vienna, not realizing that way to Vienna had to go through the Russian Zone. There were two very young soldiers with guns on their back. They stopped me and looked at the car and joked around. I had Italian plates, not American plates. I was lucky. Eventually it turned out that one of them kept pointing at the bar. The other kept pointing. Oh, he wants me to go under the bar, I drove right under the bar into the American Zone and the two soldiers were just having a good time. I saw them in my mirror, standing and jumping around, clapping their hands, awful happy I went under. It's understandable because the car was slightly below my shoulder. It was a very low car."

That was part ofwhat Linton did, being in the sport car business from 1945 when the war ended to 1985 when he sold it. After 1948, Linton raced for another twelve years where he saw the competition "change from pure sporty style to a professional one. Today's events are both types at Watkins Glen and I still attend the vintage style and reenactment one by sport groups in town and on track," said Linton.

The passing of Bill Milliken meant the passing of a friend. Linton saw Milliken at his 100th birthday parry shortly before Milliken's death.

Linton and Milliken helped usher in a new era of road racing - everything from flashy, faster cars to safer and more resilient models. That race meant something. It carried on, and stirs up the leaves of memory now some sixty-four years later.

"Ever smell castrol oil? Oh, what a sweet smell," said Bill Green when asked what he remembered about the race. "Man, it's the sweetest smelling little thing. The sounds, the sound of the Italian racing machines. It really was fun. You get worked up. When they start and come around ... that'll never go away."

Article from and courtesy of Mountain Home Magazine - September 2012

![[B] Bentley Publishers](http://assets1.bentleypublishers.com/images/bentley-logos/bp-banner-234x60-bookblue.jpg)